STOLEN GOLD

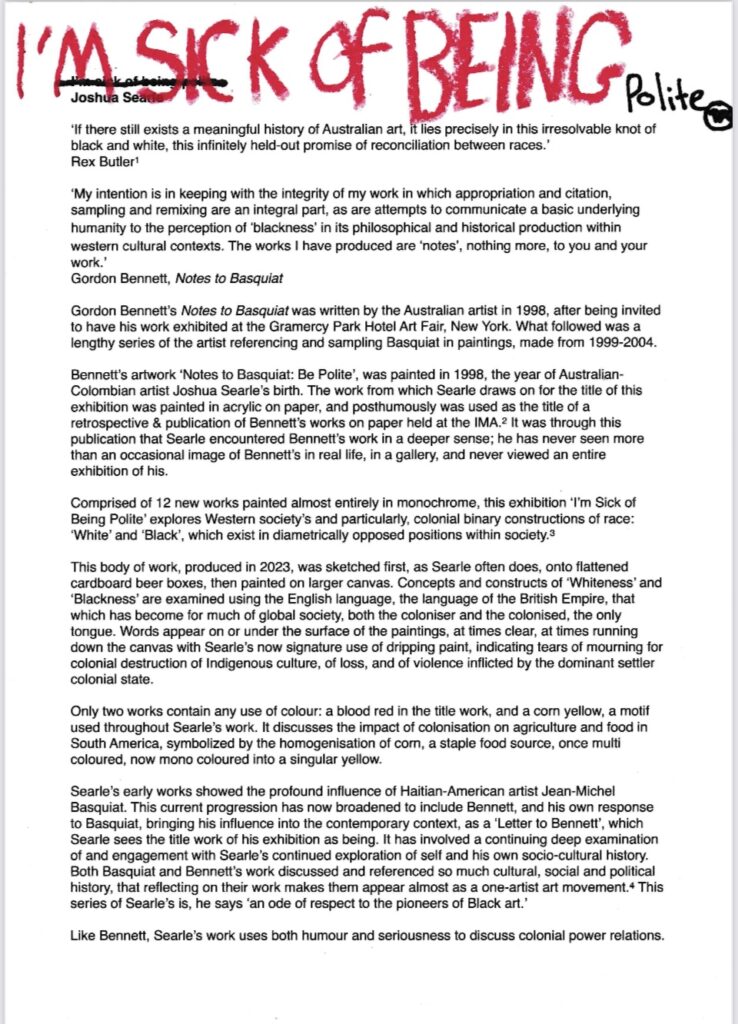

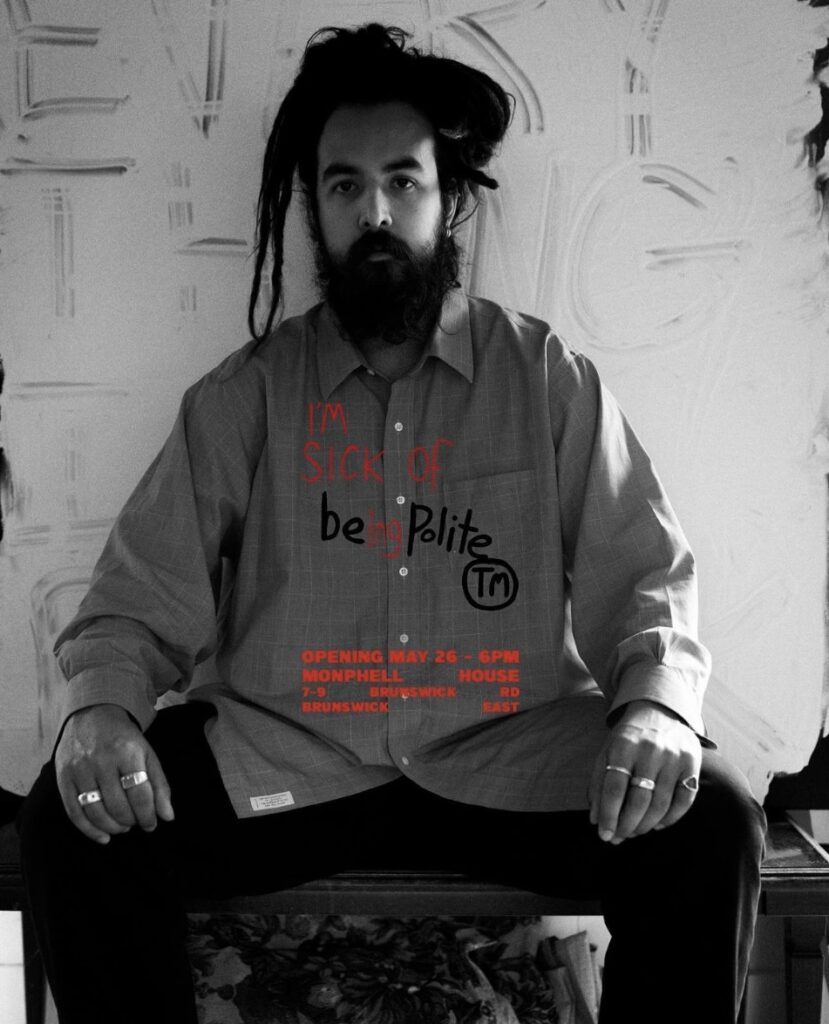

Joshua Searle

Curated by Emily McCulloch Childs

Flinders Hotel, Flinders Fringe Festival 2024

https://joshuasearle.com/page/2-STOLEN%20GOLD.html

Joshua Searle, Aztec double-headed serpent, aerosol and pigmented ink on canvas, 151.5 x 177.5 cm

Michael Grey’s ‘Pre-Columbian Art’, Thames and Hudson, 1978, was a seminal book on artworks from Central & South America held in the collections of museums, most noticeably the British Museum. Part of a series, the Thames & Hudson books on art formed a significant canonical text, appearing in school libraries across the world. They informed generations of thinking about such objects, colonial collections of museums, the origins of which were created by Empire.

The British Empire was the largest and most aggressively expansive of the European colonial superpowers. The fields of archaeology and anthropology were born as colonial activities, and thousands of objects were taken from societies across the globe to be housed in the empire’s colonial epicentre in London’s British Museum.

Joshua Searle is an Australian born artist of Colombian and settler colonial (Australian Irish) descent. He was born and raised on Bunurong/Boon Wurrung Country, on Victoria’s Mornington Peninsula, south of Melbourne. The Peninsula has a fraught colonial history, where colonial settlers cleared its forested land for farming, and was the site of a Quarantine Station built to help manage the pandemics created by the British Empire: most particularly smallpox.

When a friend gifted him a copy of Grey’s book that he had found in a local op shop, Searle’s first response was of anger at the assumption of the title. ‘Columbia’ refers to the 15th century Italian explorer Christopher Columbus, who led an exploration into South America. The categorisation of ‘Pre-Columbian’ is used to define the time period of societies in the Americas as referencing Columbus, with no recognition given to the extraordinary Indigenous societies existing independently of European endeavour.

The works in Grey’s opus include remains of exemplary cultural societies. Most significantly for Searle, and the starting point for his series, are the Quimbaya, one of the Indigenous societies of the Bogotá Plain. Famous for their skill as goldsmiths, they excelled in the lost wax technique, a technique whose invention is more commonly attributed to the ancient Greeks. The Quimbaya used gold as a way of accessing the spirit world through the animal world, and of reverence for their god, the sun. Their concept of gold was starkly different from the Europeans’, whose lust for gold was driven by greed, and who raided the Colombians of their gold as they destroyed their societies. The myth of El Dorado, which was not a city, but an Indigenous chief, originates from this area.

The impact of Spanish colonisation has impacted knowledge of Searle’s ancestry. The various small Indigenous groups became absorbed into large cities such as the capital Bogotá, which today is a cultural capital, containing 120 public galleries and museums, including El Museo del Oro (The Bogotá Museum of Gold). Although it is practically impossible to know his full identity due to this displacement and disruption wrought by colonial powers, his artwork concepts nonetheless represent the history and experiences of his ancestors. Furthermore they provide the basis for an examination into his identity as a diasporic Australian.

By referencing these artworks, called ‘objects’ or ‘artefacts’ in colonial lexicon, in painting, the medium of the Great European Masters, Searle undertakes a process of reclamation. This includes his own identity as part of the colonial diaspora, and of the works themselves, as a reclamation of art and the skill of their makers (the peoples of the Bogotá plain are known as amongst the world’s finest goldsmiths, producing gold work so fine as to be almost filigree, and the significance of the pieces (many taken from religious ceremony).

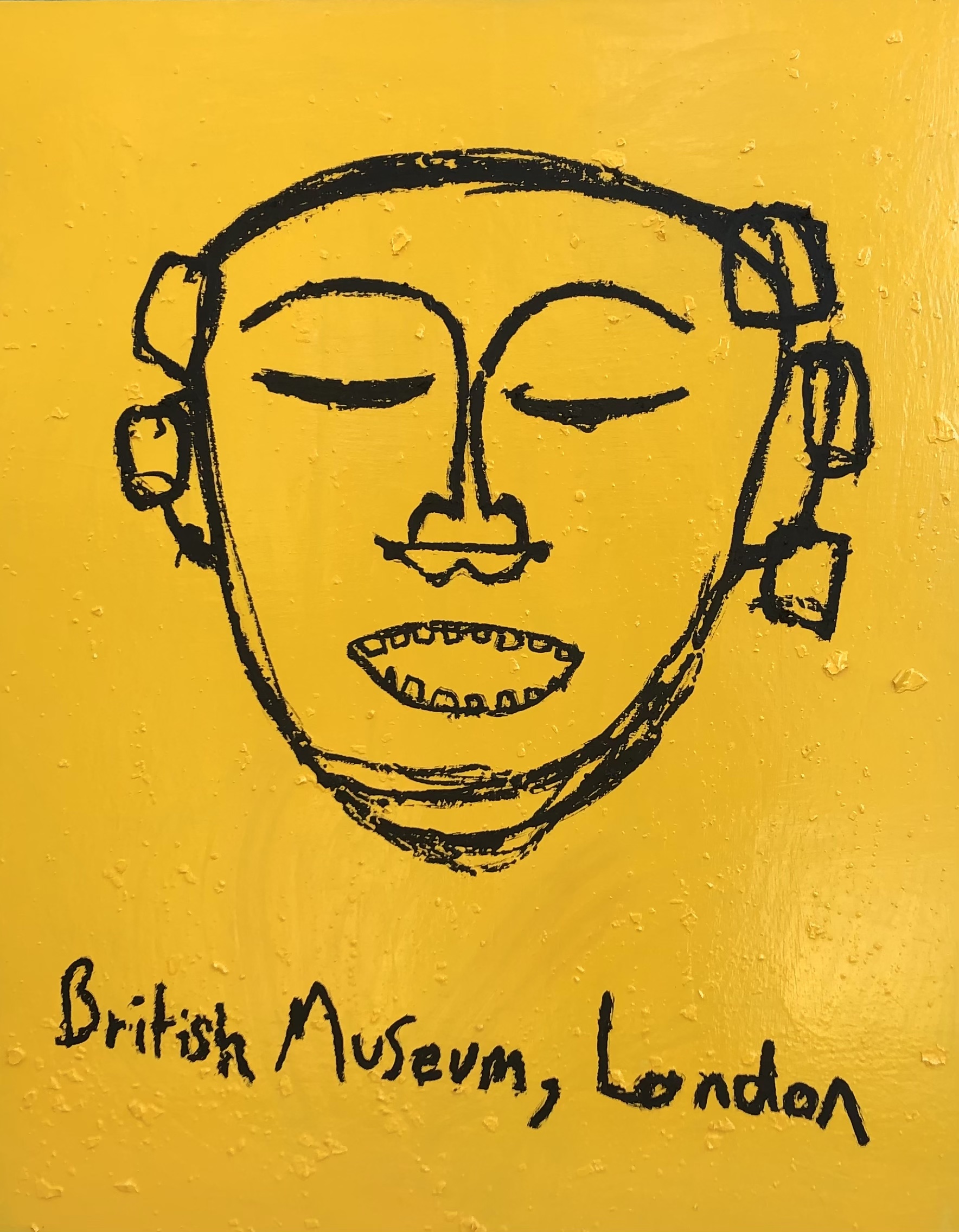

The seed for this project began with a painting of the Colombian gold mask featured in the book, held in the collection of the British Museum. Titled ‘British Museum, London’, the work features a black mask on a yellow background, with black text that reads the works title underneath. It shows the way in which these works are now held as part of the stolen wealth of empire, and identified as belonging to the British.

This work inspired the creation of a significant body of new work. He embarked on a series of sketches, done on cardboard in his studio, in oil pastel and permanent marker or ink. Each one explores an image: an Aztec double-headed serpent, a Colossal Olmec head, a ceramic Tiahuanaco Llama, a gold Colombian figure. Many of these are held in museum collections around the world, most significantly in the British Museum.

This initial examination of collective culture identity and societal impact led to a more individual personal exploration in sketches. These include works exploring his own family’s identity and impact of colonisation, and his own loss of language and cultural knowledge.

From these sketches, Searle then created a further body of paintings, done in a variety of paint: acrylic, enamel, oil stick, spray paint, artist’s ink.

Created using a process of research and development, examining Colombia and Australia’s past and colonialism, the works held in the British Museum and Colombian museums, conversations and interviews with family members, they now form a major body of work: ‘STOLEN GOLD’ and ‘STOLEN GOLD in monochrome’.

These paintings are striking in colour, style, scale and power. Often reduced down to the line work of the object, they create direct, emotional impact. The colours and use of materials such as spray paint bring them into the contemporary age, into Searle’s generation.The works draw upon the strength and skills of his ancestors, the great artists and societies of Central America, as an affirmation of sophistication and complexity, the antithesis of the othering mythology created by the colonial machine.

They are bold and political, but also very personal. Through them, the artist has undergone a fundamental reclamation of self. He has learnt of complex and skilled societies, whose artists created works of such skill they are still not fully understood today. Whilst living on land far away from these societies, this project has led him to discover much hidden history, which he then brings the audience into, enlightening them and leading them to explore their own past and other cultures.

The monochromatic works bring us even further into a reduced set of commentary on our current society, and where the artist sits in the world, how he sees and what he feels. It is socio-cultural but also again deeply personal, and we are fortunate to be given a view into his mind and its reflections of the past and contemporary world.

Emily McCulloch Childs, 2024

Texts:

Michael Grey, Pre-Columbian art, Thames & Hudson UK, 1978

Clemencia Plazas, Amelicia Santacruz Alvarez, Meyby Rios Cardenas, Hector Garcia Botero, Molas: Capas De Sabiduría, Layers of Wisdom, Museo Del Oro, Bogota, Colombia, 2017, 2021.

https://www.britishmuseum.org/

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Quimbaya

Julie Jones, ed., The art of Precolumbian gold: the Jan Mitchell collection, Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1985 https://libmma.contentdm.oclc.org/digital/collection/p15324coll10/id/119535

El Dorado: City of Gold

Lost Cities with Albert Lin, National Geographic

El Dorado: Power and Gold in Ancient Colombia Exhibition, British Museum 2013

https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2013/oct/15/british-museum-el-dorado-exhibition

Recent Comments