We Are Tiwi: The art and artists of Munupi Arts

We are the Tiwi. Tiwi is we the people. Tiwi is my people, we that lived for thousands of years on these beautiful islands. Tiwi is different to mainland Australian Aboriginals. The Tiwi culture is different: the language is different. My people, the Tiwi people, we belong to this place – the islands – Bathurst and Melville Island – all these islands belong to my people the Tiwi.

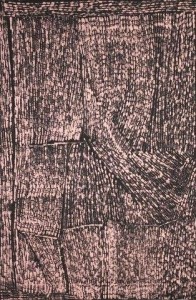

ochre on linen,

120 x 80 cm. Munupi Arts.

Pedro Wonaeamirri, Tiwi Statement in Tiwi: art, history, culture [i]

Sophisticated geometric design and meditative mark making, a balanced fusion of contemporary adaptation and classical tradition, and the strength of generations of culturally significant families underlie the Munupi Arts & Crafts Association. The art centre exemplifies what is unique about Tiwi life and culture: a distinct art style, a balance of male and female power and status, a variety of artistic skills: painting, weaving, craft, textile design, ceramics, sculpture, printmaking. The artists of Munupi are adept at all these forms of art.

Located in Pirlangimpi community on the large Melville Island, over the Aspley Straight from Darwin, Munupi Arts is now well into its third decade as a successful art centre. It has in recent years blossomed into a new life brought about through the art practice of older masters, bringing a renewed energy and traditional vigour to the art.

Foremost amongst these masters are elders Cornelia Tipuamantumeri and the late Justin Puruntatameri. I visited Munupi in 2012 to research the art centre as a curator, art historian and writer, and to interview Puruntatameri about the extensive Tiwi resistance at nearby Fort Dundas (Punata), the first British settlement in the Northern Territory. I found him waiting for me one morning at his spot at the back of the art centre, surrounded by his children and grandchildren. While we spoke, they listened attentively. He was a great teacher, a man of much knowledge. His extensive knowledge of local flora and fauna had been published[ii], he had been featured in The Australian newspaper as the most senior traditional leader in the small Melville Island community of Pirlangimpi, a great new artist drawing comparison to Cy Twombly and Jasper Johns, a ‘distinct’ voice of the old Tiwi[iii]: indeed, he was the most respected ‘culture man’ on both the Tiwi Islands.[iv]

Puruntatameri was born at Kadipuwu, next to the miscalculated site where the British would build their short-lived fort.[v] His knowledge of the fort, which lasted from 1824-9, was extensive; he told me, during our visit there, of events and features not previously documented. Of a bakery, which I have not noted on any of the archaeological records[vi], of how the Tiwi believed the British were there for treasure, for gold, of his grandfather being shot in the knee by the British, the bullet wound healed by his people’s ‘bush medicine’[vii]. Together with Munupi staff we walked around the old fort and trenches, commenting on our amazement that the British would think trenches would be any use against the Tiwi spears (perhaps they were confusing the Tiwi with Maori?). He showed me the two tutini he had made, those famous sculpture headstones made in the final stage of the pukumani ceremony.

Previous scholars have noted the tutini made for a white woman’s grave at the fort; Puruntatameri told me his were for the doctor and officer, the famous Green and Gold, who had been killed by the Tiwi as retribution for the British capture of their warrior Tambu, an act of war[viii]. I asked him why he had made these beautiful works for outsiders who had settled on his people’s land in such a brutal way. ‘I felt sorry for them,’ he said ‘having no headstone.’[ix]

This is revealing of the Tiwi’s generosity and nature, as it is of their use of art to express the deep cycles of life; birth, creation, death, and to communicate with each other and with outsiders. Early scholars of this art described the immense symbolic detail involved, wherein every painted line and dot in a bark painting or sculpture denotes a symbolic hieroglyph[x]. This hidden symbolism continues in the contemporary art movement today: in paintings by Munupi foundational artists such Reppie Anne Papajua (Orsto), Thecla Bernadette Puruntatameri and Francesca Puruntatameri, the acclaimed, award-winning artists Susan Wanji Wanji and Nina Puruntatameri, middle-generation strong Tiwi culture women Carol Puruntatameri, Delores Tipuamantumirri, Fiona Puruntatameri and Paulina Puruntatameri, and the new generation artists Natalie Puantulura and Debbie Coombes.

It is significant that most of this exhibition’s artists are women; Munupi was founded in the 1980s as a women’s craft and printmaking centre, combined with the pottery established by Eddie Puruntatameri, first chairperson of Munupi. The pottery is continued by his son, the expert ceramicist Robert Puruntatameri.[xi] Munupi artists have experimented in a variety of painting mediums, including ochre, acrylic and gouache; nowadays most of their contemporary work is done in traditional ochre, that natural, wonderful, ceremonial paint. Ochre gives their work a strong sense of ceremonial tradition but also allows for contemporary developments and interpretations of classical themes. The pared-down black and white ochre, seen beautifully in the work of Nina Puruntatameri, Josephine Burak and Fiona Puruntatameri, highlights the graphic elements of their designs.

The subtle warmth of the often rare pink ochre is worked expertly by Cornelia Tipuamantumeri, a perfect contrast to her black ochre background. Her works produce an emotional response in the viewer; they convey a deep calmness, but also a depth of cultural knowledge, not simplistically understood. Perhaps their detailed dot and line design evolves from her background as a skilled weaver.

It is astounding the myriad ways Munupi artists can work with the three classic tones of red, black and yellow. Black and yellow are Pirlangimpi colours, their prized football team, Imalu, has its name from the tiger; these colours are theirs. The Kulama ceremony, one of the most significant ceremonies on the Islands, features with these colours as the theme of many of these works. Nina Puruntatameri’s paintings of this semi-secret-sacred ceremony are an example of expert contemporary rendering of this ceremony: they illustrate its significance in their impressive power and beauty, giving us a glimpse of hidden depths involved in long and extensive ritual and religious ceremony.

The works in this exhibition may have a commonality in their mythological underpinnings but display a surprising array of stylistic variation. Carol Puruntatameri’s works depict organic-like forms in an earthy gentle palette of rich deep yellows and light browns. A painting by Daphne Wonaemirri is striking in its geometrical patterning, a clever, classic hallmark of Tiwi design. Debbie Coombs’ whimsical works are a great example of Tiwi anthropological observation, depicting the travels of peoples in vehicles and boats, more modern day realities that have become Tiwi through marks in their design. Delores Tipuamantumirri, daughter of Cornelia, paints strongly traditional designs and also more abstracted developments.

In complete contrast are the linear design graphs of Fiona Puruntatameri, perhaps the painter in this exhibition who most recalls the notable genre of Tiwi textile art. Her balanced compositions in black and white are intricate and aesthetically pleasing. Josephine Burak shares this reduced palette and geometry but her works are more fluid; they contains joyous explosions of light, perhaps evoking the great expressions of Tiwi ceremonial dance.

Only one artist, Natalie Puantulura, works in a multi-coloured palette. Yet her paintings lose none of the Munupi focus on balance, composition, and graphic elements. The beauty of the environment on the densely forested Melville Island is recalled to me by the evocation of natural beauty as seen in the works of Sheila Puruntatameri, Paulina Puruntatameri and Marie Simplicia Tipuamantumirri.

Thecla Bernadette Puruntatameri’s work is completely different again: joyous energetic shapes surge upwards in a dance-like movement; their combined design recalls the famed Tiwi barbed spears yet represent fire which is vital for both hunting and regeneration of country.

Justin Puruntatameri passed away just several months after I visited and interviewed him. His passing has left a great gap in the Tiwi world and the Australian arts. It is wonderful to see his legacy continuing on through the work of Munupi artists, and I think he would have been most proud of this exhibition, another great addition to the magnificent cultural lexicon that is the artists of Munupi, and a proud continuation of their fundamental assertion of their identity: ‘We are Tiwi’.

Emily McCulloch Childs

The name of the late artist Justin Puruntatameri is used with his family’s permission. The author wishes to thank the staff and artists of Munupi Arts for their generosity and time.

[i] Pedro Wonaeamirri in Jennifer Isaacs, Tiwi: art, history, culture, The Miegunyah Press, Melbourne University Publishing, 2012, p.viii.

[ii]Justin Puruntatameri et al, Tiwi Plants and Animals: Aboriginal flora and Fauna knowledge from Bathurst and Melville Islands, Northern Australia, Parks and Wildlife Commission of the Northern Territory and the Tiwi land Council, Darwin, NT, 2001.

[iii] Nicolas Rothwell, Old memories from a new master, The Australian, 4 November 2011.

[iv] Jennifer Isaacs, Justin Puruntatameri biography, Tiwi: art, history, culture, p. 273.

[v] ibid, p. 272.

[vi] Several archaeological digs have been carried out at Fort Dundas/Punata, with the support of the Tiwi Land Council, the most extensive being by Eleanor Crosby, 1975, and Clayton Fredericksen, 2002.

[vii] This may have been the young boy who was shot as noted in Fredericksen and others, Clayton Fredericksen, Caring for history: Tiwi and archaeological narratives of Fort Dundas/Punata, Melville Island, Australia, World Archaeology, Vol. 34(2), Routledge, 2002, p. 288-302.

[viii] The story of Tambu’s (Tambu Tipungwuti) capture and subsequent escape is detailed by Tiwi people themselves and features in most writing on the events at Fort Dundas/Punata. It was also described to me in detail by Puruntatameri, who showed me the geographic locations of Tambu’s escape: he swam over the Aspley Straight from Fort Dundas/Punata to one of two small islands (regardless of crocodiles and sharks). From there he rested a while before swimming across to the other island, then back around to Melville Island proper, where he travelled around the back of the British and gathered his people, at his place called Ranku, who then warned the Munupi people, and they all planned a stealth attack on the British. This was a carefully planned, stealth ambush. One of the British escaped and alerted the Fort. The British then descended with guns, so the Tiwi ran into the mangroves. The famous barbed Tiwi spears, some up to 16 feet long, are impossible to get out. The Tiwi shot their spears through the windows of the hospital, and then they speared the commissariat officer John Green and Doctor John Gold, who were, Puruntatameri said, walking from the Fort to have a shower. They speared the doctor in the back. I believe this was a strategic attack on the doctor, for the British then had no medical help to deal with malaria, scurvy and the like, became ill, and the fort was abandoned. Puruntatameri also told me the Tiwi wondered why the British decided to establish their fort where they did, as there was little fresh water.

[ix] Justin’s daughter Paulina Puruntatameri, known as Jedda, accompanied us on our visit to Fort Dundas/Punata. A strongly active preserver of her people’s culture, she is current Chairperson of Munupi, and working towards creating a cultural museum there, and on digital archiving and on the repatriation of Tiwi artefacts. When visiting Fort Dundas/Punata she wittily commented to me ‘The British believed in terra nullius, because Tiwi hid in the bushes, they couldn’t see us, so they thought there might be no one here.’ We then discussed how that situation must have quickly changed when the first of the barbed spears flew from the bush.

[x] See Charles Mountford’s classic work The Tiwi, their Art, Myth and Ceremony, Phoenix House, London, 1958, which documents the intricate symbolic detail of mythology, landscape, religion and law particularly in Tiwi bark paintings of the people of Melville Island.

[xi] Isaacs, p.260.

Recent Comments