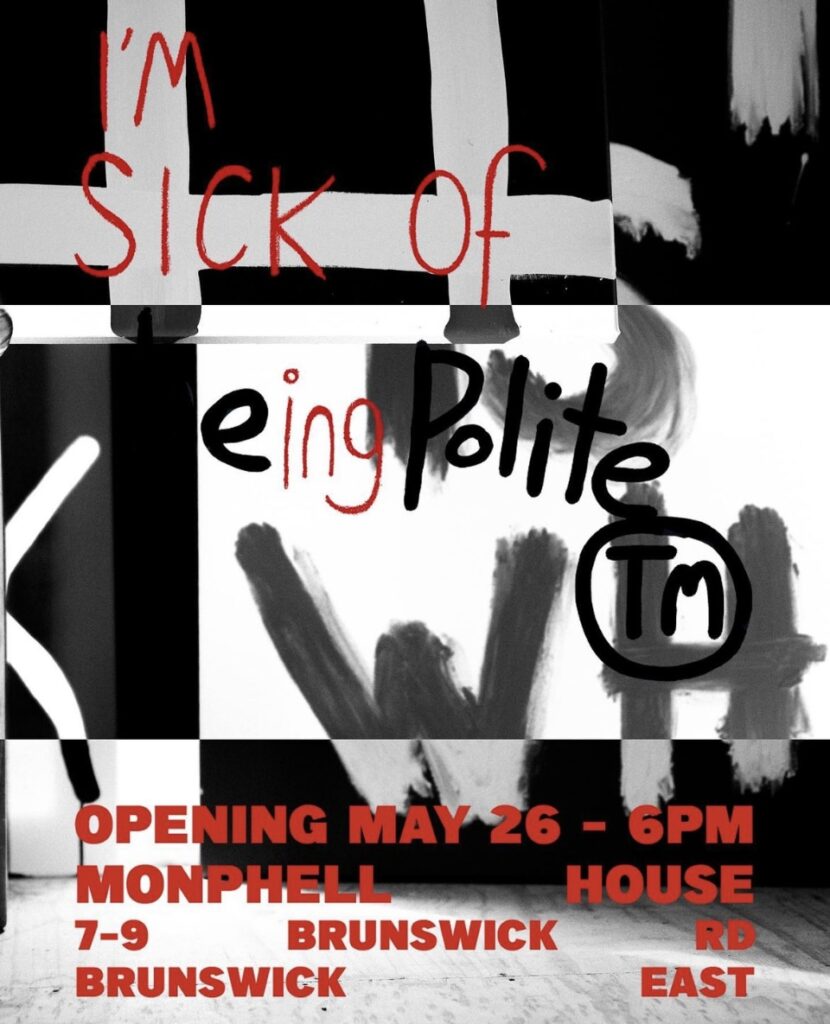

I’m sick of being polite

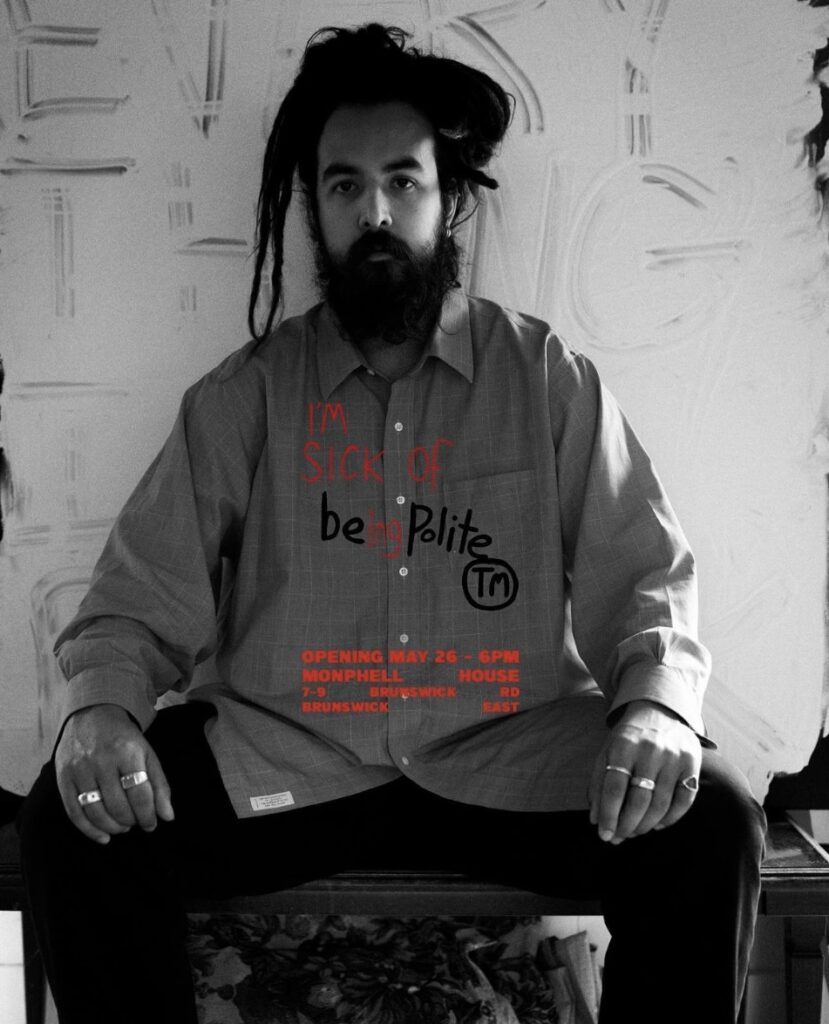

Joshua Searle

Monphell House

7-9 Brunswick Road

Brunswick East

Opening May 26 2023

6-10 pm

Runs May 26-28 2023

Web: Joshua Searle I’m Sick of Being Polite

‘If there still exists a meaningful history of Australian art, it lies precisely in this irresolvable knot of black and white, this infinitely held-out promise of reconciliation between races.’1

Rex Butler

‘My intention is in keeping with the integrity of my work in which appropriation and citation, sampling and remixing are an integral part, as are attempts to communicate a basic underlying humanity to the perception of ‘blackness’ in its philosophical and historical production within western cultural contexts. The works I have produced are ‘notes’, nothing more, to you and your work.’

Gordon Bennett, Notes to Basquiat

Gordon Bennett’s Notes to Basquiat was written by the Australian artist in 1998, after being invited to have his work exhibited at the Gramercy Park Hotel Art Fair, New York. What followed was a lengthy series of the artist referencing and sampling Basquiat in paintings, made from 1999-2004.

Bennett’s artwork ‘Notes to Basquiat: Be Polite’, was painted in 1998, the year of Australian-Colombian artist Joshua Searle’s birth. The work from which Searle draws on for the title of this exhibition was painted in acrylic on paper, and posthumously was used as the title of a retrospective & publication of Bennett’s works on paper held at the IMA.2 It was through this publication that Searle encountered Bennett’s work in a deeper sense; he has never seen more than an occasional image of Bennett’s in real life, in a gallery, and never viewed an entire exhibition of his.

Comprised of 12 new works painted almost entirely in monochrome, this exhibition ‘I’m Sick of Being Polite’ explores Western society’s and particularly, colonial binary constructions of race: ‘White’ and ‘Black’, which exist in diametrically opposed positions within society.3

This body of work, produced in 2023, was sketched first, as Searle often does, onto flattened cardboard beer boxes, then painted on larger canvas. Concepts and constructs of ‘Whiteness’ and ‘Blackness’ are examined using the English language, the language of the British Empire, that which has become for much of global society, both the coloniser and the colonised, the only tongue. Words appear on or under the surface of the paintings, at times clear, at times running down the canvas with Searle’s now signature use of dripping paint, indicating tears of mourning for colonial destruction of Indigenous culture, of loss, and of violence inflicted by the dominant settler colonial state.

Only two works contain any use of colour: a blood red in the title work, and a corn yellow, a motif used throughout Searle’s work. It discusses the impact of colonisation on agriculture and food in South America, symbolized by the homogenisation of corn, a staple food source, once multi coloured, now mono coloured into a singular yellow.

Searle’s early works showed the profound influence of Haitian-American artist Jean-Michel Basquiat. This current progression has now broadened to include Bennett, and his own response to Basquiat, bringing his influence into the contemporary context, as a ‘Letter to Bennett’, which Searle sees the title work of his exhibition as being. It has involved a continuing deep examination of and engagement with Searle’s continued exploration of self and his own socio-cultural history. Both Basquiat and Bennett’s work discussed and referenced so much cultural, social and political history, that reflecting on their work makes them appear almost as a one-artist art movement.4 This series of Searle’s is, he says ‘an ode of respect to the pioneers of Black art.’

Like Bennett, Searle’s work uses both humour and seriousness to discuss colonial power relations. The title work ‘I’m Sick of Being Polite’ includes red in its black on white text, which may be a reference to blood. For Bennett,

‘Blood is a potent symbol and has historically been a measure of Aboriginality.

In the past ‘Quadroon’, was a socially acceptable term used to label Indigenous

people as a way of establishing genetic heredity. The ‘purer’ the bloodlines, the

more Aboriginal you were. Mixing of pure ‘blood’ with European ‘blood’ was feared

by Europeans, ‘authenticity’ was at risk and identity diluted.’5

‘I’m Sick of Being Polite’ is also a reference by Searle to the history of the laws of racial etiquette, and to the politics around social existence. For Black and Indigenous people living under frontier colonialism, behaviour was governed by the state, with punishment for deviation from a continual behavioural policing and self-policing.6 This authoritarian history continues today, wherein people of colour must constantly self-police their behaviour, in order not to be perceived as embodiments of racial stereotypes, which are always negative. Research into this has found that such constant self-policing comes at great psychological cost, leading to burn out and impact on mental health.7

This exhibition considers the changing historical constructs of ‘whiteness’ and ‘blackness’, within Searle’s diasporic country, Australia. ‘The idea of what is ‘black’ and what is ‘white’ is’, he says, ‘a construct. It has grown, shrunk, and morphed over time. There was a time in Australia, for example, where Italians weren’t considered white.’ In his work ‘What is White’, he references the ways in which ‘the terms of whiteness are continually changing, for example under the White Australia policy, there was a ‘One drop policy’ denoting ‘Blackness’.’ Affirmations of reclamation of Blackness are considered in works such as ‘I LOVE BLACK’, which was inspired by listening to a podcast interview with artist Jammie Holmes, who when asked what his favourite colour is, stated simply ‘I love black’. Searle says this work is a response to ‘Othering language, Colonial language that has the aim of ‘Othering’ Black and Indigenous peoples.’ It is a reaffirming statement of Blackness, viewing the self positively, with the black paint bleeding through into white text.

The work ‘Everything is Black’ concerns the origins of culture. There are, Searle says, ‘lots of things today that we have and use, that we don’t know the origins of. These include foods that have been colonised: such as South American foods: potatoes, tomatoes, corn.’ Like humans, these foods have become colonised, their Indigenous history erased.

The musical inspiration and references that resonated with Basquiat and Bennett also find resonance for Searle with his similar love for hip hop. His work ‘Black Child’ was inspired by a Biggie Smalls album cover, and the song ‘Black Child’ by Birdz, a Butchulla hip hop artist, featuring Mojo Juju, a Wiradjuri Filipino artist, the music video filmed on Boon Wurrung/Bunurong Country, where Searle was born, raised, and still lives. It symbolises the perpetual perception of being seen a black child in colonised society, yet has an Afro hairstyle that is broken, referencing a halo, a Black angel child.

A significant section of this exhibition concerns state violence against ‘othered’ bodies, which is viewed through the militant authorities of the settler-colonial culture, exemplified through the violence of police. These works include ‘Cops and Robbers’: a two-part set of canvases that work together, which play on the idea of black or white hoods. A black hood, as balaclava, symbolises Black crime, a white hood the Ku Klux Klan. In this context, black and white cultural signifiers shift context illustrating the multiple ways of viewing race. Another ‘double’ work, ‘Cell 1’ and ‘Cell 2’ was inspired by a performance at the Black Entertainment Television awards, and depict life size prison doors, illustrating how incarceration is an important factor around Blackness and Whiteness.

The work ‘Hooded Heads Can’t Speak’ symbolises what Searle calls ‘Silencing’, referencing American state torture of political prisoners at Guantanomo Bay, and the Australian state torturing of young Aboriginal people using spit hoods. This tool is used to silence, to ‘put a hood over somebody takes their rights away, is further used to torture them.’ This is explored further in the work ‘Hooded Heads Can’t Be Heard’. Here the text is redacted like military documents, symbolising the way in which activists and dissidents can ‘vanish’, by being taken by authorities in certain countries. The work contains ‘some corn and a business suit, a hood, scribbled in finger-paint.’ Corn appears again, an enduring symbol of Searle’s Colombian heritage, food being a significant part of identity.

The work ‘Protesthis’ draws inspiration from activist and artist Ai Wei Wei, with Searle examining state violence towards protestors. It examines inequality, human rights abuses and displays of power.

In 2007, Rex Butler wrote that Bennett could be considered as the ‘last ‘’Australian’’ artist,’ with his retrospective being not only of him, but ‘of a whole tradition of art in this country.’8 Since, we have seen a rich generation of artists influenced by and evolving from Bennett’s school, an explosion of voices reclaiming the ‘other side’ of colonisation and identity, an encyclopaedia of Blak, Brown, and ‘Othered’ artists, exploring and protesting the oppression of the continued Colonial State. With this new body of work, Searle adds to this important centralisation of resistance and discussion within “Australian” art, and the art of settler-colonies internationally, as a reclamation, assertion and expression of voices and imagery that is entirely crucial to our society.

1 Rex Butler, THE REVOLUTIONARY COLOURING HISTORY (review of Gordon Bennett retrospective, NGV), The Australian, 31/8/07

2 ‘Gordon Bennett: Be Polite™’ curated by Aileen Burns and Johan Lundh, Institute of Modern Art, Brisbane where it was first presented in October 2015, touring then to the Perth Institute of Contemporary Arts in 2016, Contemporary Art Gallery, Vancouver, 2017 and McMaster Museum of Art, Hamilton, Canada, 2018. From this exhibition a publication was produced, edited by the curators, with essays by Helen Hughes, Ian McLean and Julie Nagam, IMA and Sternburg Press (Berlin), 2016.

3 We can recall in particular the work of Franz Fanon, ‘Black Skin, White Masks’, which discusses colonisation, white supremacy and ‘phobogenesis’, a thing or person that elicits “irrational feelings of dread, fear, and hate” in a subject, and whose threat is often exaggerated. In the context of race, Fanon postulates that the black person is a phobogenic object, sparking anxiety in the eyes of white subjects.

Derek Hook, “Fanon and the Psychoanalysis of Racism,” https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Black_Skin,_White_Masks

4 Rex Butler wrote: ‘There has been one revolution at least within living memory in Australian art: it was the coming together in 1971 of the schoolteacher Geoffrey Bardon and the old men of Papunya to produce the phenomenon of contemporary Aboriginal art.

But there has perhaps been a second revolution that is in a way its echo, its extension, even its negation. We might date it from some time around 1987 when the artist Gordon Bennett started making his first paintings while attending Brisbane’s Queensland College of Art.’ Rex Butler, op cit

5 ‘As an Australian of both Aboriginal and Anglo Celtic descent, Bennett felt he had no access to his Indigenous heritage. He states: ‘The traditionalist studies of Anthropology and Ethnography have thus tended to reinforce popular romantic beliefs of an ‘authentic’ Aboriginality associated with the ‘Dreaming’ and images of ‘primitive’ desert people, thereby supporting the popular judgment that only remote ‘full–bloods’ are real Aborigines.’ Blood also speaks to the violence of the frontier and the continued violence of current colonial occupation, it ‘exposes the truth of colonial occupation – it was a ‘bloody’ conquest.’ https://www.ngv.vic.gov.au/school_resource/gordon-bennett/

6 ‘The whole intent of Jim Crow etiquette boiled down to one simple rule: blacks must demonstrate their inferiority to whites by actions, words, and manners. Laws supported this racist code of behavior whenever racial customs started to weaken or breakdown in practice’ Jim Crow Museum

https://www.ferris.edu/HTMLS/news/jimcrow/question/2006/september.htm

7https://hbr.org/2019/11/the-costs-of-codeswitching

8 Rex Butler, ibid

Emily McCulloch Childs, May 2023