Bulay(i): Buku-Larrnggay Mulka and The Indigenous Jewellery Project

Catalogue essay for Australian Design Centre exhibition: Bulay(i): Buku-Larrnggay Mulka & The Indigenous Jewellery Project

Exhibition images by Simon Cardwell

As one of Australia’s most prestigious and internationally recognised Aboriginal-owned art centres, Buku-Larrŋggay Mulka in Yirrkala, the Yolŋu community outside of Nhulunbuy (Gove) in North East Arnhem Land, is well-recognised for both practicing and maintaining artistic and cultural tradition and creating exciting innovation with its art.

An art centre is a not for profit community business owned by Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander artists, run by a board, with staff appointed as managers or co-ordinators, as they are still called at Buku-Larrnggay. It is a uniquely Australian invention, invented long before the acronyms NFP and NTO became buzz words in the new business model world.

Established in 1976, Buku-Larrnggay Mulka works with many artists living in Yirrkala and its satellite homelands within a several hundred km radius. Artists have exhibited in many of Australia’s top public and commercial galleries, including as part of the Biennale of Sydney at the MCA, the NGA, AGNSW, NGV, NMA and internationally including the Istanbul Biennial and in the exhibition Marking the Infinite, Newcomb Museum of Art, touring USA.

The art centre has a close proximity to an airport and accommodation at nearby Nhulunbuy. Along with its fame for significance in land rights, it is rich in art and music (home of Yothu Yindi and family with nearby Elcho Island’s the late Dr. G. Yunupiŋgu), and the home of the yiḏaki or dhambiḻpiḻ (didgeridoo), and Garma Festival.

On any given day, one may encounter collectors and gallery directors from America, professors from Canberra, top Australian public gallery curators, important politicians (often a Prime Minister), or famous musicians, actors or artists. This is amidst the constant stream of fascinated tourists visiting for the rich culture, beautiful tropical scenery and world-class fresh seafood that the region has to offer, especially now that Yirrkala boasts a Yolŋu-owned and operated tourism business, Lirrwi Tourism.

Buku-Larrŋggay Mulka has long been a leading studio in printmaking, and is world famous for its tradition of bark painting and sculpture, with large commissions including The Kerry Stokes Collection of 95 larrakitj poles and accompanying encyclopedic book.

More recently these artists have explored new media in their art, working with computer programming, film and virtual reality with the Mulka Project. The centre’s dedicated archival and film project, it is now one of its major forces in working with younger generations full of the artistic genius that seems to spring up everywhere in this historically significant place.

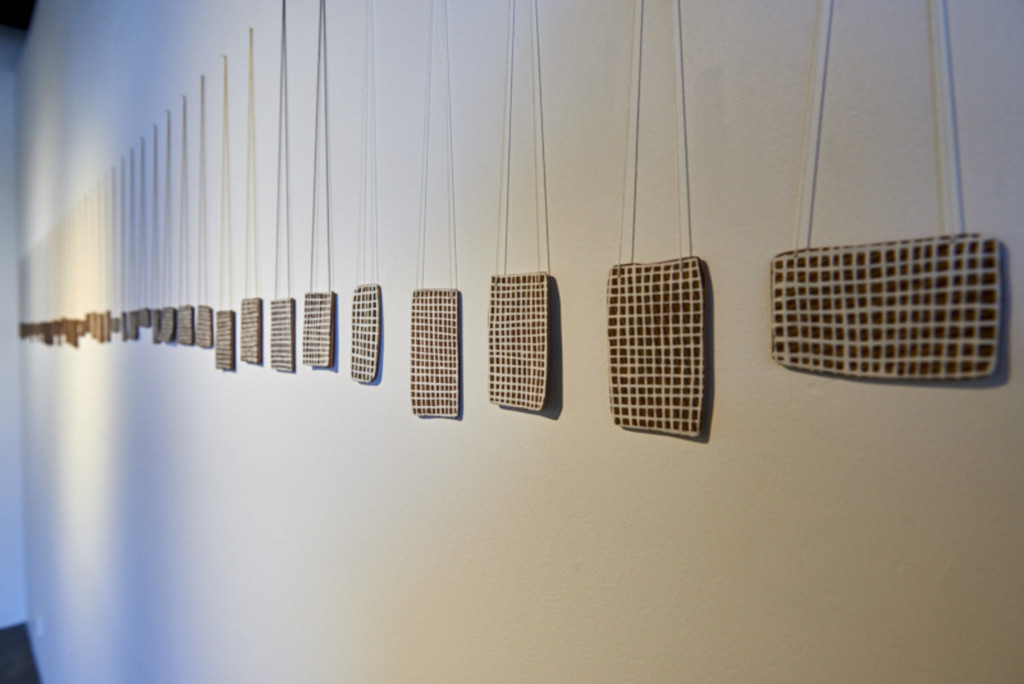

As well as painting, sculpture, new media and printmaking, craft has always been well maintained here. The art centre is a treasure trove of stunning fibre work by Yolŋu women, inventive small wooden carvings and objects and of course jewellery.

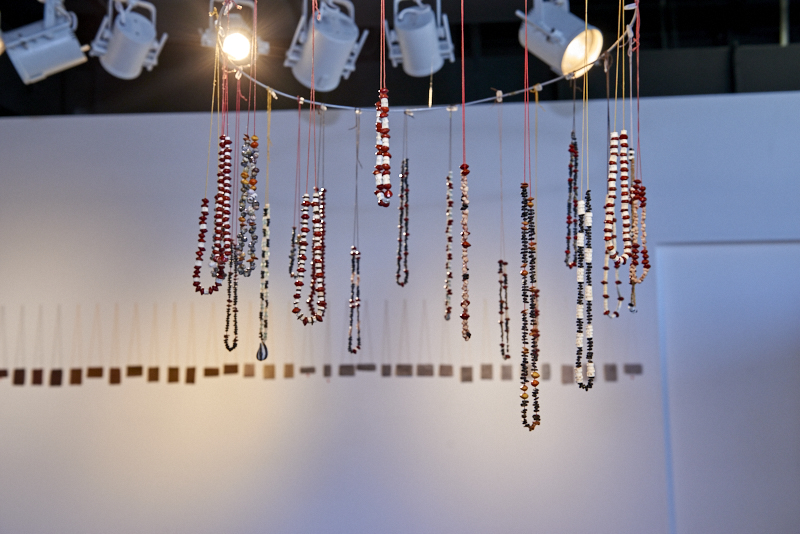

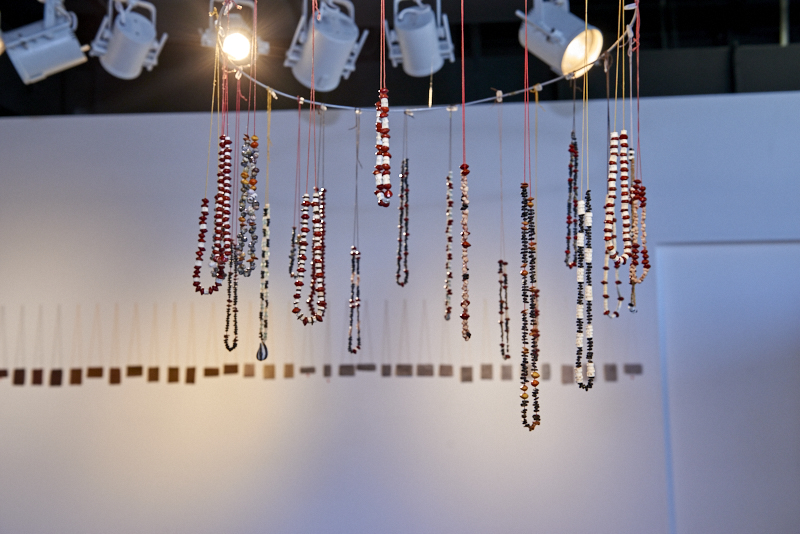

Strands of necklaces, called girring’girring in Yolŋu matha, the lingua franca of the region’s many languages, hang in the art centre, delighting visitors who visit in a seemingly endless stream.

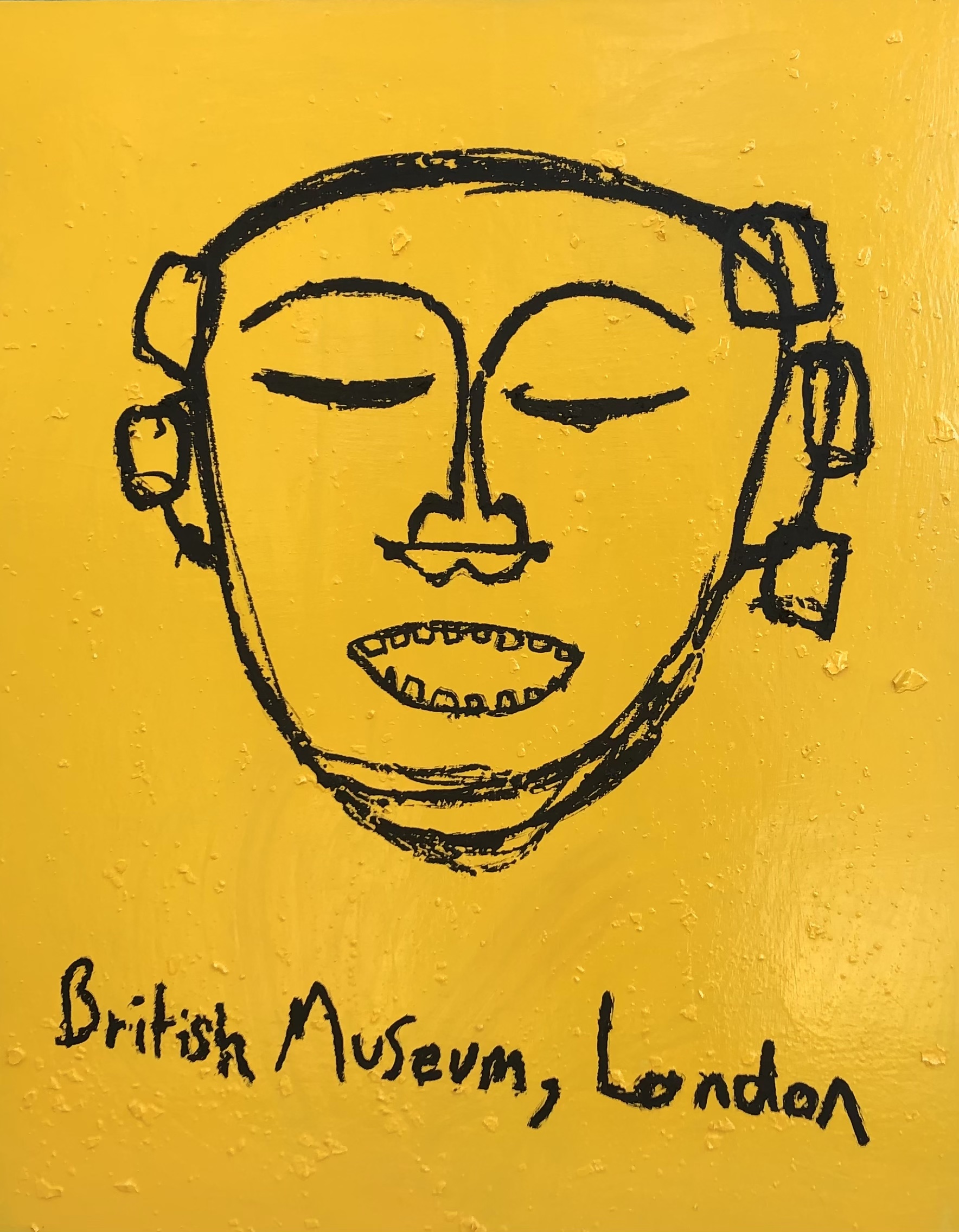

Whilst the jewellery practice from this region, consisting mostly of necklaces strung with extremely fine seed beads, shells and shark vertebrae, has long been noted and admired, appearing in the groundbreaking exhibition Art on a String (Louise Hamby and Diana Young, Object: Australian Design Centre for Craft & Design, 2001), Bulay(i) is the first jewellery-focused project held at Buku-Larrŋgay Mulka.

Bulay(i)

Yolngu Matha language

rich jewellery, gold, precious stones, bronze, treasure.

Bulay(i) is ‘old Yolngu’. It may refer to the treasures of the neighbouring Macassans, over the sea, who Yolngu have had a long relationship with. All of this exhibition is Bulay(i): not just the metals, the first metal jewellery made at Yirrkala. The natural materials are also precious.

Bulay(i) is the fourth Indigenous contemporary jewellery project undertaken by The Indigenous Jewellery Project. IJP is national: and has ranged from workshops in the Torres Strait Islands, to Ernabella (Pukatja) in Pitjantjatjara lands in northern South Australia, to Haasts Bluff on Luritja land in the Western Desert, and now with the Yolngu in north east Arnhem Land. It is the first contemporary jewellery project held at Buku-Larrnggay Mulka.

The Indigenous Jewellery Project is an attempt to address a gap, or rather two gaps. The first national contemporary jewellery project undertaken with Indigenous jewellers, it aims to provide a presence of Indigenous jewellers within the Australian contemporary jewellery context, and a contemporary jewellery presence within the Aboriginal art context.

The project has been inspired by many things: my collection of Indigenous jewellery, interactions with contemporary jewellers, being half New Zealander and seeing the now tradition of Maori contemporary jewellery, similar projects within Aboriginal art undertaken in printmaking (Basil Hall, Martin King), or weaving (Arnhem Land, Tjanpi Desert Weavers). The ways in which Arnhem Land art centres have worked with their skilled craftspeople in weaving to showcase the sophistication of their art.

IJP began because of an interest, and a need. Along the way in my path as a curator, I had the good fortune to cross paths with contemporary jewellers. They have taught me much about their genre of art, and through my own research into Aboriginal jewellery and body adornment I have seen the need for more development in this area. Of course it is largely a women’s art practice; although Aboriginal men do make jewellery and every one of our workshops has had male jewellers, from age six to adult. But it is undoubtably Aboriginal jewellery’s status as ‘women’s craft’ that has kept it out of the canon of Art.

The artists already working in such a way, such as Lola Greeno, Maree Clarke, and Julie Gough, for example, have illustrated the potential for the use of traditional Indigenous jewellery with contemporary jewellery as a powerful art medium created for the gallery space.

But for jewellers who live in the very remote areas, there is little access to contemporary jewellery influences, teachers or materials. We must come to them.

This project is a vision for a new kind of curating. I call it interactive or pro-active curating. Beyond the role of being a receiver of art, the concept of ‘curator’ may have originated from the museum, but is evolving. A new curatorial premise can include being the initiator of art projects. Curators are in a position to see the gaps. We have minds similar to artists, but yet not exactly like theirs. We don’t have their impetus to communicate visually, to make with the hands, but we understand them and what they create effects us strongly. We want to help bring their creations to the world. We are the Dhuwa to their Yirritja: we complement each other, we are in a symbiosis: this is our natural state.

Girring’girring

‘All art springs from the soil.’

Geoffrey Bardon

Traditional Yolngu jewellery is now well-known and recognised mainly due to its use of incredibly fine seed beads, often strung on long necklaces that can be wrapped around the neck two or even three times. These long necklaces are a direct descendent of ceremonial necklaces.

I recall first becoming familiar with these necklaces, and being astonished at the fineness of them, the skill of the makers. I was almost intimidated by their fineness, especially when compared to the larger necklaces of Central Australia I was more used to. And then there was the shark and fish cartilage. What jewellery genius eons ago had first thought to string beads from this material? The whiteness of the cartilage has such pure beauty: it recalls white ochre, and the whiteness of ceremonial feathers. The shape of the cartilage is sculptural, with small rhythmic holes like dots made by a skilled artist. The skill of these jewellers is in making art from nature’s materials.

It took several events to get to this stage: the first was discovering that Buku-Larrnggay Mulka’s long-term art co-ordinator, Will Stubbs, shared a similar fascination for these necklaces and their tradition as I do. During a visit to the art centre, he showed me a collection of girring’girring, made by women of this Miwatj region, including out on very remote tiny islands, that is significantly beautiful. Two of these necklaces have since been exhibited, at Tactile Arts, Darwin. They are comprised of shark cartilage but also the blue bone of parrot fish, an example we have in this exhibition is by the exemplary necklace jeweller Madinydjarr Yirrinyina #2 Yunupiŋu.

Together Will and I set out on making a jewellery project at Buku-Larrnggay Mulka happen.

The second event was the knowledge of contemporary jeweller and UNSW lecturer Melinda Young, whose become my partner in jewels with much of The Indigenous Jewellery Project. Before the workshops Melinda researched ways we could help fix the problems of the necklaces, which to us was mainly the fact that they were strung on fishing line: not something a jeweller would consider a suitable stringing material. Melinda helped bring in proper jeweller’s materials, and during the first workshop in particular she undertook much research & development into the issues with the necklaces.

She had science experiments going on the verandah of the house we were staying in, little bits of wire with seed beads on them, in various states. When her research was concluded she was overjoyed: the seed beads had ‘worked’ in the way she wanted them to. From observing the Yolngu jewellers, she noticed how they used fresh seeds, allowing them to dry on their string. The amount the seed shrank when dry caused gaps in the necklaces. Now, strung in our workshops, they have gaps but they look beautiful as there is no plastic fishing line to be seen. In fact, now that they are strung on silk, they are made from 100 % natural materials. They are now much stronger, more durable and infinitely more wearable than ever before.

The workshops

‘Art is a way of establishing connections between people across cultures.’

Professor Howard Morphy, Djalkiri: We are standing on their names, Blue Mud Bay (Djambawa Marawili, Marrirra Marawili, Liyawaday Wirrpanda, Marrnyula Mununggurr, Mulkun Wirrpanda participated in a printmaking workshop with master printmaker Basil Hall at the community of Yilpara, North East Arnhem Land, working alongside Fiona Hall, John Wolseley, Jörg Schmeisser and Judy Watson, 2009)

‘When you aren’t pushing uphill: when it just flows, when you aren’t forcing it: that’s when you have entered the Aboriginal space, and it’s working.’

Kim Mahood, advice to me, Mulan community, Tanami desert, Western Australia, August 2017

Each time we arrive in North East Arnhem Land it seems like it is to some kind of ceremony. Twice now there’s been the new music festival, Yarrapay, on. For the second workshop as I arrived there appeared a perfect rainbow, arcing over the community store with its mural of the famous artists and leaders, adorned in traditional Yolngu body adornment. According to artist and Bulay(i) jeweller Marrnyula Mununggurr, it was welcoming us.

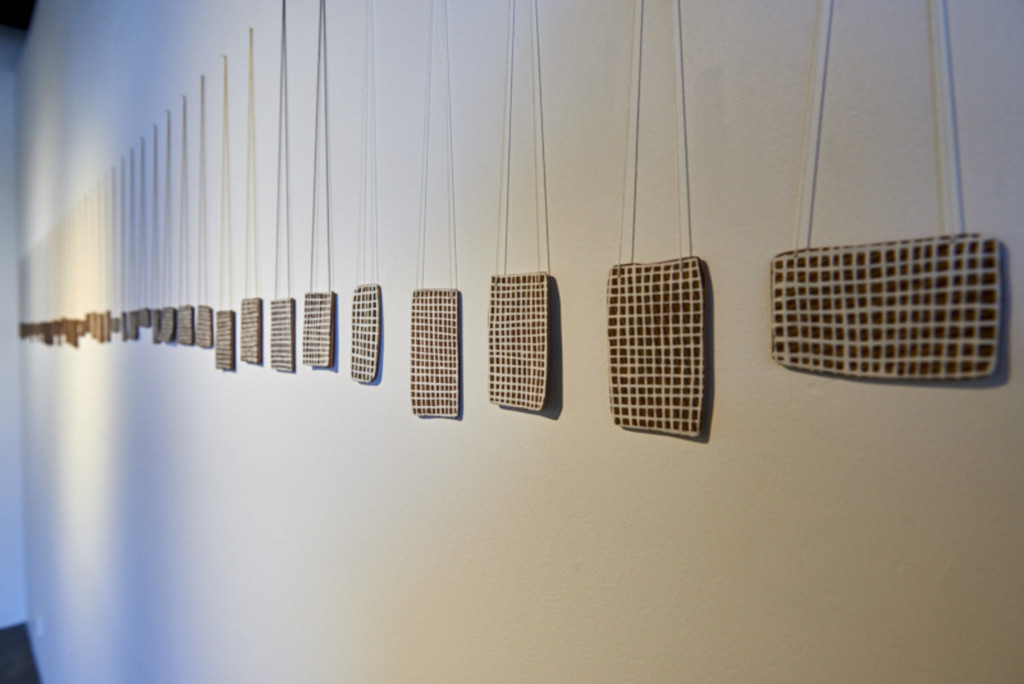

The rhythm of the day begins, lost in a rhythm of tiny seed beads, tiny shell beads, wax carving, all kinds of shapes and creatures and designs appearing.

We run out of beads and go gathering: this is just down the road usually, to where the jungle, the bush that surrounds us, encroaches upon the community. Thick tangles of vines, flowers: it all looks the same to me, but the jewellers spot each and every different kind of seed bead plant. They show me how and where to look: once you get your eye in it’s easy to spot the green seed pods everywhere. It takes me a while to figure out which seeds, encased inside their pods like tiny perfect rows of sleeping bead babes, are perfect for beads, and which are too old to use.

The best ones are green/yellow to orange, not too young or too old, turning red. The seeds start off green and move to yellow to orange to red to brown. They are as transformative as the mythological shapeshifter creator beings. The jewellers use these different colours to give design and rhythm to their necklaces.

Yolngu are saltwater people, and the sea is part of their traditional country.

Reference to the sea abounds in their art. The sea is fundamental to Bulay(i): in the materials, and subject matter of many totemic marine animals. There are myriad names in Yolngu matha for different kinds of fish, at different stages of their lives,

The natural world is always present in Yirrkala, and many of its artists live in homelands by the sea, or go ‘hunting’ on the weekends: gathering sea foods.

The first workshop established the core Bulay(i) crew. Making jewellery as a group seems to be an incredibly strong bonding exercise. It should be used by the United Nations, in mediation, in Parliament, to stop wars. Our core jewellers include Marrnyula Mununggurr: an artist, daughter of the significant artist Nongirrnga Marawili, granddaughter of famed artist and leader Wonggu Mununggurr, Madatjula Yunupingu, the great earring maker, and Madinydjarr Yirrinyina #2 Yunupiŋu, an exemplary traditional jeweller. She lives on her homeland of Wanduway, and only comes into Yirrkala occasionally. We were lucky enough to have her in the workshops, and she made an impressive amount of very fine girring’girring. Her young daughters also have her talent for jewellery: they took to lost wax instantly.

For this project, I became a workshop co-ordinator, project manager, and jeweller’s assistant. I have now become entrenched within a family of jewellers who share amongst us a common understanding of the significance of jewellery. We delight in the meditative process of gathering: seeds and shells, of sitting on the ground and making by hand, the rhythm of carving jeweller’s wax, of creating something that you can wear on the body, gift to a friend to wear, hang on a wall.

Working in the studio with the jewellers every day over several workshops, we became profoundly effected by the experience. We began to learn Yolngu words, to build up our Balanda mouths to learn the trickier Yolngu pronunciation for sounds that we don’t have in English. One day Marrnyula, an artist I’ve always connected with and who has adopted me as her ‘yapa’ (sister), gave me my Yolngu name: Dhonyin, the Javanese file snake, one of the three manifestations of the Rainbow Serpent within Yolngu culture. When we asked her why I was given this name, she said because I looked like a file snake: it was my hair, she said, yellow and brown, like the snake’s body, and with rainbow colours: this water snake creates rainbow patterns on the water as it moves through water lilies.

Symbol of creation, fertility, transformation. Dhonyin the Rainbow Serpent creates beauty, a rainbow, from water and leaves. For this exhibition, Marrnyula created a series of Dhonyin pendants: they symbolise this hugely significant creation spirit. Perhaps Marrnyula named me Dhonyin also because I created this project: to transform, to evolve, to elevate. But it is these jewellers who have the true creation magic: to create beauty and art. The Bulay(i) jewellers create beauty from twisted vines and tiny seed pods and shells. Dhonyin symbolises our transformation and the transformation of Yolngu jewellery: no longer confined to the art centre in Yirrkala, now ready to go out into the world and to transform us all.

Emily McCulloch Childs, October 2017

I would like to thank Melinda Young, who has been so invaluable as workshop teacher, curatorial advisor, and much more on this project, production assistant Jody Thompson, Will Stubbs, Merrkirrwuy Ganambarr-Stubbs, Siena Stubbs, Edwina Circuitt, staff, board and artists of Buku-Larrnggay Mulka, the community of Yirrkala, the Mununggurr family, the Yunupingu family, all the Bulay(i) jewellers, and the Ministry for the Arts Indigenous Languages & Arts Program for supporting this project.

Recent Comments