Recently I was at an exhibition opening of art from the APY Lands, a vast, stunningly beautiful and largely unknown (to outsiders) area of Australia[1]. A region of big skies and open land, hidden  rockholes filled with creation beings, occasional mountain ranges and desert oak forests, a land still alive and still sung. An Aṉaŋu[2] cultural leader[3] who had made a particularly moving speech during the opening spoke to me afterwards of the ecological catastrophes affecting his people’s lands. This was the first thing he spoke to me about, with a sense of great urgency and despair. To those not so familiar with the only true Australian art[4], this may have seemed just one aspect of the arts’ subject matter or of the exhibition itself. But it wasn’t: it was the central theme: underpinning all the complex law and religion, the colour and beauty and humour and creation stories. The man was reaching out to me as a writer and curator who could perhaps help educate the rest of Australia, and the world, about the battles against the areas of a death, spreading, a formidable disease. Its name? Buffel grass. Brought in on the hooves of cattle, it is devastating large regions of fragile, beautiful Australia.

rockholes filled with creation beings, occasional mountain ranges and desert oak forests, a land still alive and still sung. An Aṉaŋu[2] cultural leader[3] who had made a particularly moving speech during the opening spoke to me afterwards of the ecological catastrophes affecting his people’s lands. This was the first thing he spoke to me about, with a sense of great urgency and despair. To those not so familiar with the only true Australian art[4], this may have seemed just one aspect of the arts’ subject matter or of the exhibition itself. But it wasn’t: it was the central theme: underpinning all the complex law and religion, the colour and beauty and humour and creation stories. The man was reaching out to me as a writer and curator who could perhaps help educate the rest of Australia, and the world, about the battles against the areas of a death, spreading, a formidable disease. Its name? Buffel grass. Brought in on the hooves of cattle, it is devastating large regions of fragile, beautiful Australia.

Due to previous art research trips through The Lands, I knew first-hand the devastation brought about by introduced camels, feral cats, rabbits and other pests. The feral camels, over a million of them, kill everything: they strip leaves and bark from trees, effectively ring barking them. They die in the waterholes, the lifeblood of these areas, destroying the entire eco-system for everything from the little marsupials, like the ninu (bilby) and the little birds, right up to the malu (kangaroo) and kalaya (emu).

Aṉaŋu are ethno-botanists, they know complex connections of plants, animals, water and land; the ways in which birds and animals spread plant seeds. So when animals die, plants die. Everything dies. But the buffel grass: this was something new again. Traditional, highly developed Aṉaŋu land management techniques weren’t working. ‘You can’t burn it; it doesn’t burn.’ the leader said to me. It was destroying the native grasses, another major life source. His words stayed with me.

Speaking with him, I was reminded of a dear Aṉaŋu elder and artist I had the privilege to work with, the late Tjilpi R. Kankapankatja. He was a genius level ethno-botanist, whom scientists from ANU travelled to study with. He knew the names, medicinal and other properties of thousands of plants. He painted these, in paint on canvas, with love and joy. His works were delightfully, superficially naïve, but underlying their directness were decades of extensive complex botanical study and knowledge. He was an example of how art can encompass and communicate many seemingly disparate modes of knowledge.

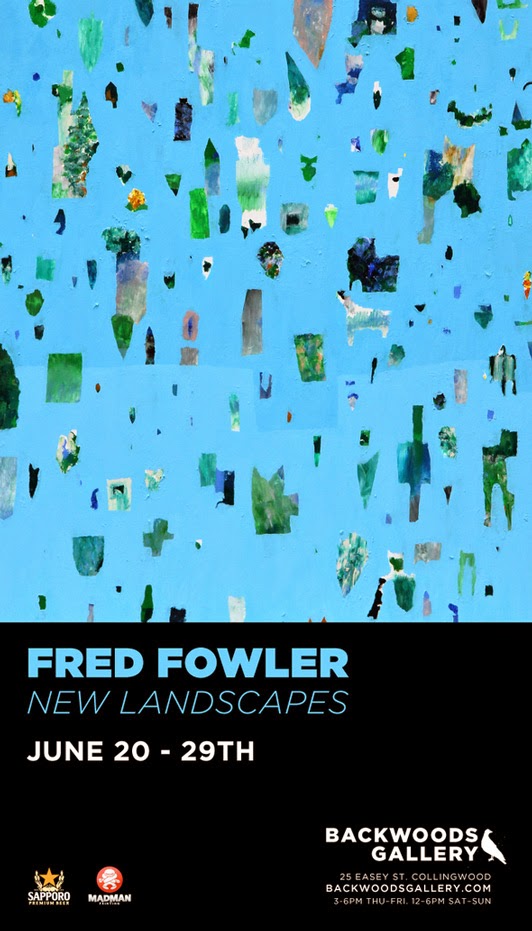

The title of Fred Fowler’s exhibition, New Landscapes, is simple, but telling. Australia is one of the oldest continents on earth, with the oldest continuous cultures. But for the Europeans who arrived here in the eighteenth century, it was a strange and new land. For their descendants, it still is, in many ways. The land of Australia is written in our historical literature as being ‘strange’ ‘foreign’ ‘other’, most of it ‘desert’ ‘dry’ ‘arid’ ‘hot’ and uninhabitable. Its ‘remoteness’ is commented on: but it is ‘remote’ only depending on where you stand, where you come from. If you are Aṉaŋu, the APY Lands are in fact the centre of the universe; Melbourne and Sydney are remote, strange, foreign and often harsh and unforgiving places. This land has been demonized as much as its original inhabitants, in a way that is inescapably linked.

It took European-Australian artists over a hundred years to even begin to capture some of the reality of the Australian landscape, and to cease to see it through overtly European eyes. The landscapes of Heysen, Roberts and Streeton were groundbreaking in their evocation of the bush, its misty blue palette, or dry red earth under a blazing blue sky. Yet their work was of the heroic bushman; an Anglo-Celtic or Saxon male hero, against all odds, surviving in a harsh environment. Man sought to dominate and tame the bush, not to live with it (although Streeton, to his great credit, was an early environmentalist and protector of Australia’s old-growth forests).

It wasn’t until the Antipodean school that such a tranquil, and rather mistaken, telling of settlement and environment began to be challenged. Boyd, Nolan, Williams and Drysdale in particular broke with the conventions of Australian landscape painting and painted a more accurate reflection of the world around them. Boyd included Aboriginal women and their plights in his landscape in his pioneering 1950s ‘Half-Caste Bride’ series. Nolan explored the interior of Australia and revisited the heroic myth, and found that it wasn’t so heroic after all. Williams and Drysdale pushed the boundaries of landscape painting at the time, reflecting the often abstracted character of aspects of the Australian landscape; its angular trees and un-European palette, its rounded, often amorphous red rocks. They introduced black into their landscape palette, evoking the true contrast of the land and its forms, far from a perpetual gentile muted European softness.

Fowler’s approach, whilst this series, he says, cannot be understood as conventional landscape painting, reflects the changes that have occurred in our understanding of our environs and the past as non-Indigenous Australians since then. Fowler has, as he says ‘used the vessel of landscape painting to explore ideas about native and invasive species, both animal and human’. His work is subtle, didactic and articulate: the works are neither brutal expressions of a self-aware artists’ frustration with the present state of environmental destruction occurring in this country, nor harshly realistic depictions of racial oppression and the inequality between the colonisers and the subaltern; and yet, nor are they superficially pretty, decorative paintings of trees and bush. They are aesthetically intriguing paintings containing a subtle yet intellectual and empathetic message, with careful composition of colour and form. Strange shapes hover in a colour field, they are animalistic, but not always animals. Some recall collage, parts of skulls, crystals, buildings, trees, birds, ghosts, or abstracted tribal designs.

Despite his good length of time as an exhibiting artist, these new works continue to explore some of Fowler’s background in street art and graffiti; some of the raw, urgent shapes revisit Basquiat whose influence upon the world continues. Often painted in oil stick, occasionally shapes appear like watercolour; the artist’s methodology of his technique reflects his subject. A variety of surfaces are created, some multi-hued, some rough, others smooth. The collage-like shapes often appear either floating or behind the canvas, giving us hints of other worlds, of depths beyond our immediate perception.

The titles reflect the wide-range of Australian environments: ‘Fire Coral (Colonial Marine Organism)’, depicts the fragile, threatened seas, Queensland’s Great Barrier Reef with its vast coral systems, the colonial sea trades (fishing, pearling, whaling, trepanging) which brought with them the violent underside of Imperial trade: slavery, prostitution, disease, violence, colonial sea trades which developed into modern day incursions: dredging, mining, over-fishing, shipping, polluting. And the seas as a modern day, unequal battleground over borders.

In creating this series, the artist had considered the work of several other artists working in the field of colonialism and identity. Paola Pivi’s work ‘One Love’, with its depiction of white animals in a colonial type landscape, shown at Queensland’s GOMA, ‘contains the resonance of eighteenth-century European paintings which depicted ‘exotic’ species from disparate geographies, brought to Europe via colonial trade routes for the entertainment of the wealthy. Pivi also underlines the connotations of ‘white’ identity and racist histories.’[5]

The late Yorta Yorta-Scottish artist Lin Onus, one of the most significant artists of his generation, also resonates with Fowler: his work exploring both issues of colonialism and Australian identity often used the symbolism of animals. Onus’ famous depiction of himself and his good mate, gallerist and artist Michael Eather, as ‘X and Ray’, a dingo and a stingray, are amongst the most positive depictions of the mateship across Indigenous and non-Indigenous peoples made to date. But it is Onus’ famous ‘Fruit Bats’ that Fowler says has most influenced his current series directly. Defiant statements of anti-colonialism, these clusters of bats, their bodies painted in the rarrk Onus was given permission to use by Arnhem Land artists, take over the most suburban of all Australian signifiers, the Hills Hoist. In typical Onus fashion, the intellect of the artist drove him to conceive the installation using humour, wit and whimsy to catch the viewer off-guard and suspend their political defensive disbelief.[6]

Significantly, Fowler’s New Landscapes series has an engagement with these complex issues of colonialism, identity, and Indigenous and non-Indigenous interactions and issues, without feeling the need to do as so many non-Indigenous artists seem fit, to appropriate Aboriginal art, as a perhaps well-meaning but inadvertently offensive sort of homage. The works in this exhibition are painted in the artist’s own stylistic oeuvre, he has felt no need to cheat, by lifting designs used in paintings from the great artists from the Western Desert or other areas, to give us easy clues as to what they are about.

His landscape subjects comprise broad-ranging themes: ‘The Ecological Society of Australia’ ‘Merging of Diversification’ ‘A Brief History of Colonisation’ which evoke these questions of identity and concerns for the impact of colonising powers upon Indigenous people and lands.

Some works are more site-specific, the border of New South Wales and Queensland, a border which brings to my mind the towns of Moree and Boggabilla, as seen in the films of Ivan Sen, who explores the complexity of Indigenous and non-Indigenous identities, particularly amongst youth, and issues of racism. The Bournda Nature Reserve, a national park in New South Wales. And the most famous of all Australian natural landmarks, perhaps with the exception of Uluru or the Great Barrier Reef, one so familiar for its settler architecture that it is almost easy to forget that it is even a site of nature, Sydney Harbour.

Fowler’s new landscapes evoke all that is ancient and beautiful about this land, and simultaneously, subtly, that which is more recent, brutal and confronting. They are a much needed, thoughtful exploration of these issues of land, animals, plants and humans, adding much to the discussion of Australia’s past and its present condition.

Emily McCulloch Childs

Fred Fowler, ‘New Landscapes’, Backwoods Gallery, Melbourne, 20-29th June, 2014

[1] The APY Lands are the Aṉaŋu (human being, person) Pitjantjatjara (language group) Yankunytjatjara (language group) lands, in northern South Australia. They comprise some 103,000 square kilometres; have 7 art centres, a wealth of brilliant artists practicing in many mediums from craft to painting, and a richness of unique and delicate flora and fauna.

[2] Aṉaŋu is the word for ‘human being, person’ in Pitjantjatjara, which is how these people identify themselves in the contemporary age.

[3] Cultural leader Lee Brady.

[4] Art critic Alan McCulloch used to say ‘the only true Australian art is that which is made by Aboriginal people’, and reflected this belief in his writings in Meanjin, The Herald and other publications.

[5] Paola Pivi, http://www.qagoma.qld.gov.au/exhibitions/past/2010/21st_Century/artists/paola_pivi

[6] Lin Onus, Fruit Bats, sculpture, 1991, held in the collection of the Art Gallery of New South Wales, see George Alexander in Tradition today: Indigenous art in Australia, Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney, 2004. Rarrk is the unique style of cross-hatching used by Arnhem Land artists, and is owned by them, which must not be used without permission. See also Margo Neale et al, Urban Dingo: the art and life of Lin Onus, 1948-1996, Queensland Art Gallery, 2000.